THE NATURAL BASIS

OF

SPIRITUAL

REALITY

|

CORRESPONDENCES OF THE HEART AND LUNGS--PART 2 THE WILL AND THE UNDERSTANDING 85. We have already noted that the rule of the heart in the body corresponds to the rule of love in the mind of an individual, but most of our attention in the previous chapter was focused on applications to the Church as a whole. We have seen that the Church functions spiritually as a heart and lungs because its love corresponds to a heart and its wisdom to lungs for the service of the human race as a whole (Nos. 57 and 84). The quality of the Church is an integration of the quality of its individuals, and it is for this reason that the correspondences in each man apply also to the Church. But there is a further spiritual reason, namely, that the Lord organizes each heavenly society (of which the Church is one) into a human form. Thus there is no fundamental difference between the application of correspondences to an individual man and their application to the Church. It seems easier to envisage their application to the individual, especially when, as now, we attempt to relate particular functions in the body to those in the mind, or spirit. 86. There is a spiritual universe between the innermost soul of man and the living organs of the body (man is a microcosm, AC 6057). But every level of this universe is related to every other by correspondences. By making use of this relationship our merely natural minds can grasp spiritual verities which intuition or the rational mind urges us to accept.(1) 87. From common speech we are ready to accept that the heart is love, for as we have seen, common metaphors are often derived from correspondences (AC 4406). It is not so generally accepted that the lungs correspond to the mental faculty of understanding, perhaps because most people are confused regarding will and understanding (AC 634; DLW 361). However, it will become clear from what follows that the correspondence of the lungs is with the understanding. In the Writings, will is often used to mean love, for it is the receptacle of love, so we begin with the concept that the heart corresponds to the will or love, and the lungs to understanding or wisdom. It is therefore important to form serviceable ideas of what the will and understanding are. The meaning of will and understanding

88.Thoughtful people of all persuasions are accustomed to distinguish between the emotions and the intellect. They know that the two interact to some extent and that it is often wise to control the former by means of the latter. From this beginning one may step into the New Church world of will and understanding by regarding the will as the seat of the emotions and the understanding as the intellect. However, this is only a most external view and if not opened it can be quite misleading; emotions, for example, can sometimes be largely a condition of the body-brain unit. A truer view is to see that the will is that inmost part of man into which the Lord flows with life which expresses itself in love, and that the understanding similarly receives wisdom from Him. 89. It is difficult for man to grasp the real meaning of the understanding of truth and the will of good. The reasons for the difficulty and some aid in overcoming it are to be found in AC 634, but the angelic way of thinking about these things is described as far as natural language allows in DLW, part V. This opens with the following heading: Two receptacles and dwellings of His own, called will and understanding, have been created and formed by the Lord in man; the will for His Divine Love, and the understanding for His Divine Wisdom.As explained in AC 634 and elsewhere, these Divine qualities received in the highest part of a man's mind are above his consciousness, and they descend by degrees to the conscious mind where they are received according to the quality of that mind. Thus it is that will and understanding sometimes mean such qualities of love and wisdom as are within our conscious grasp. But again, as they are received according to the form of each man's mind, they can even mean the opposite, when will is self-will and understanding is folly. In the Writings such variant meanings are always quite clear from the context. The will is the receptacle of love but it is not identical with love neither is the understanding identical with wisdom 90. As the will is the receptacle of love it is often used to mean love. The Writings state that we may equate will and love, but this is probably only as a first approximation, for it is introduced by "Whether you say." The whole sentence is "Whether you say love or will it is the same since the will is the receptacle of love" (DLW 378 at the end). 91. There are a number of reasons for regarding this statement as a first approximation (or a general truth), but as an example of the difficulties that arise if it is applied too rigidly, consider the following. Just as the heart produces such things [other organs] on account of the varied activities it is about to perform in the body, so love produces corresponding things in its receptacle, the will, for the sake of the various affections that make up its form. (DLW 410)From this we get an idea that love acts in the will as the heart acts in the body, thus that the will corresponds to the whole body, and this is confirmed in DLW 403 where we read, "the will is the whole man." But we read elsewhere "The will corresponds to the heart" (DLW 371:iii). 92. In trying to understand these things more clearly, we wish to distinguish between the vessel (the will) and what it contains (the love). This is not now difficult for we have already seen how, in the language of the Writings, the kingdom of the heart includes the blood vessels and the blood, and thus how the heart is united with the whole body, and rules all the other organs by serving them (Nos. 74-78). This means that in our reading we must not always confine our ideas of the heart to that particular organ itself. Instead, we may think of the correspondence of the will with the kingdom of the heart as it extends throughout the whole body, and of the correspondence of love with the heart itself within the chest. In other words, as the whole body is full of blood vessels and blood within different organs, so the will is full of loves of many kinds, yet all with a common purpose depending on the ruling love. There has been occasion earlier (No. 61) to distinguish between a vessel and its contents (although vessels are so often used in the Word to signify the contents). But the vessel is external and so, in our thoughts as we pass from the vessel, e.g., "a cup," to the contents, e.g., "cold water," we are led from externals towards internals, and thus in the direction of heaven and the Lord. 93. Similarly, when we read of the heart we may think of the will, and when we think of the will we may think of the love it can receive from the Lord and how He dwells with man. From contemplating these things we may, at times, be led to think of the Lord's love as being for the whole human race, and as expressing itself through individuals and their uses towards the neighbor. So we become concerned with how love can express itself in use. Then our concept of the will as being the whole man and as corresponding to the heart, and blood vessels, and blood itself throughout the whole body helps us to realize the richness and variety of the uses that love can perform, although enthroned, as it were, and protected in the chest. In this way a distinction between love and the will can be useful. However, when-ever we observe such a distinction it is important to remember that love is not in its receptacle, the will, as water in a cup, but that it penetrates and activates because it is life from the Lord. The will without love would be a corpse. 94. A similar distinction must apply to the understanding and wisdom, but it is not so obvious, for as the lungs cannot work without blood from the heart, so neither can the understanding work unless impelled by some form of love from the will. Since, however, the understanding may be filled with foolishness which it may later replace with wisdom, it is clear that the understanding is also a kind of receptacle or organ. 95. Although it seems important to make these distinctions if we wish to think deeply, the Writings often do not do so, perhaps because a true understanding must necessarily house wisdom and a genuine will must necessarily be the dwelling of a good love. We may therefore continue to say the heart corresponds to love and the lungs to wisdom, invoking the distinctions only where necessary. The correspondences of the heart and lungs include all psychology 96. This is because psychology means knowledge of the psyche (or soul), and we read: In view of the complexities of the human mind, how can such a statement be justified? The things that follow in DLW concerning the heart and lungs are relatively simple, and what we are taught about will and understanding in the Writings, are vast, complex, and difficult to understand. It is clear that in the Writings the Lord was providing for the future, when much more would be known about the heart and lungs. But even now all the known detail of the anatomy of these organs could scarcely suffice to illustrate what the Writings teach. Other sciences have their role, and it is one of the delights and uses of the New Church scientist to show how knowledge of the ultimates amongst which we live can provide, through correspondences, a more vivid picture of spiritual reality. 97. The assertion which provides the heading just above can only be proved by one who knows all "which can be known," etc., but it is hoped that the chapters which follow will demonstrate some of the things which can be known from the correspondences and that many more remain to be discovered. 98. Until now we have been concerned mostly with correspondences of the heart, but we need to think a little more about the lungs if we are to achieve a portion of the knowledge promised in the quotation above. 99. The correspondence of the lungs has already been mentioned because in so many places in the Writings the heart and lungs come together. Anatomically and physiologically this is an obvious convenience, because they are so closely associated, and as we would expect, the association extends into the correspondences also, since the lungs correspond to wisdom, and love without wisdom is as useless as a heart without lungs. Only active lungs correspond to wisdom 100. To be precise, we say that the understanding (or wisdom) corresponds to the respiration of the lungs. This is as stated in AC 3888. However, lungs are often spoken of without mention of respiration, for (as before noted) correspondences are really with the use or function; what are lungs apart from the respiration? It is obvious that it is only normal, healthy, active lungs that correspond to wisdom. Active lungs require a good supply of blood from the heart (which is love). The correspondence of this is that, although wisdom can only exist when truth is in the understanding (the lungs), love also is necessary, for we read that "he is wise who lives the truth from love" (AC 10331:2). We see, then, that when the truth is activated by love so as to be useful, then it is not merely truth but wisdom. Truth activated by an evil love becomes folly. Truth not activated by any love is not anything at all. It is, however, an abstraction which, if not destroyed, may become something. We see this in the state of the lungs in the embryo. Their union with the heart is sufficient only for their preservation and growth. They do not function. Most of the blood by-passes them. So we have a picture of man at the beginning of regeneration. His love is sufficient to cause the truth with him to grow and to maintain it in a potentially useful form, but it does not as yet function in his life. It is not wisdom. His "heart's blood," the driving force of his life, by-passes the truths stored in his memory, and his life is not really good. 101. In some such way as this we must distinguish between truth and wisdom. Nevertheless, in order to study the ways in which truth is united with good, and so becomes wisdom, we often speak of it as though it were already wisdom; prolepsis rather than inaccuracy. The importance of the understanding to the life of the mind is shown by the importance of the lungs to the life of the body 102. This statement is the obverse of DLW 399 which says, "the love or will is the very life of man." This is so true that we cannot but assent to it wholeheartedly, but the facts brought forward in support of it introduce a soupcon of doubt. They are like salt in food; clearly they are deliberately introduced, as salt is deliberately added to food. We therefore examine them more closely. 103. At first we receive an impression that the importance of the understanding is being depreciated. It seems to be established that the life of the mind depends on the will alone: [The heart] may act apart from the cooperation of the lungs [as] is evident from cases of suffocation and swooning. From this it can be seen that, as the subsidiary life of the body depends on the heart alone, so likewise the life of the mind depends on the will alone, and in the same way the will lives when thought has ceased… (DLW 399)But one may be excused for thinking that the life of the body does not depend on the heart alone. Many other organs are necessary, as is also pointed out in DLW 367 in which we read, "the whole exists from the parts, and the parts continue to exist from the whole." 104. Swooning and suffocation are temporary conditions;

a drowned man will not survive unless he receives artificial respiration

promptly. Swooning and suffocation are usually the result of sickness or

accident, and we may therefore think of them as disorderly as well as temporary

Translating by correspondences, we deduce that the life of the will when

thought has ceased is temporary and disorderly. We therefore conclude that,

as a man cannot continue a normal life if his lungs are not working, so

neither can he do so if his understanding does not function. Those whose

will is not assisted by the understanding are of unsound mind.

105. Thus we can see more in DLW 399 than at first appears. As stated there the will can live when thought has ceased, but this is only for certain types and conditions of men and angels, and for us, activity of the understanding is necessary most of the time. The "joint rule" ascribed by the Writings to the heart and lungs can be understood only in terms of physiology and biochemistry 106. One of the most interesting problems arising during a study of the heart and lungs involves the predominance the Writings give to the heart. At the same time, a ruling influence is ascribed to the lungs throughout the body; that is to say, the lungs join the heart in its rule but the heart is the senior partner. It is difficult to envisage this role of the lungs without the aid of a little biochemistry, even though everyone knows that normally the whole body dies if the lungs cannot function. 107. Several passages in DLW explain the primary importance of the heart compared with the lungs, and show that this is in correspondence with the primary importance of the will compared with the understanding. There are passages which emphasize that, as the will does nothing without the understanding, so the heart does nothing without union with the lungs; it is together that they "rule" throughout the body. Some ideas about the movements of the lungs and how such movements affect the rest of the body are brought out to show how it may be that the lungs have their part to play in the joint "rule" with the heart. Here we wonder whether the limitations of natural knowledge in Swedenborg's time made it difficult for him to find the natural facts to which the wisdom of the angels corresponds.(2) We read that: All things in the body are connected so that when the lungs breathe, each and all things of the whole body are moved thereby, while at the same time also they are moved by the beating of the heart. (DLW 403)The union of the heart and lungs by blood vessels is next mentioned. This is followed by a statement about ligaments joining the cavity of the chest and other viscera: [They are]…so joined that when the lungs breathe, each and all things in general and in detail receive something from the respiratory motion…all the lower parts of the body…receive some movement through the action of the lungs.108. The union of the heart and lungs is also mentioned in Arcana Coelestia, where we find: By means of the blood vessels the heart rules in the whole of the body and in all its parts; and the lungs in all its parts by the respiration. Hence there is everywhere in the body as it were an influx of the heart into the lungs; but according to the forms there and according to the states. (AC 3887; see also 3889)109. But, one may ask, How can the heart flow into the lungs in remote parts of the body, even "as it were"? How can the lungs rule in remote parts of the body by respiration? Can "some movement" be enough for "rule"? What is meant by "according to the forms and according to the states"? How can "some movement through the action of the lungs" be interpreted as a union of heart and lungs? We hesitate to ask such critical questions but it seems as though it was foreseen that many of us would ask questions, and that we would feel diffident in so doing, for at the end of DLW 403 we are encouraged by these words: but examine the connections well and survey them with anatomical eye, and afterwards, according to the connections, observe their cooperation with the breathing lungs and with the heart, and then think of understanding in place of lungs, and of will instead of heart, and you will see.If with "anatomical eye," why not also with the physiological, biochemical and, in general, scientific eye? 110. We read, "all things receive something from the respiratory motion" (DLW 403). What is the something they receive? The reduction of pressure in the chest during inspiration of air is believed to help in the return of venous blood to the heart. This could be considered one way in which the lungs cooperate with the heart (although it is really the chest rather than the lungs). But it can hardly be the "something" that all parts receive. Later it is said that they receive "some movement." Now, it would seem that "movement" in the sense of a small displacement in space, such as, for example, the pulse in an artery, would be a trivial matter, apart from the actual pumping effect. From his knowledge of spiritual things, it was very clear to Swedenborg that a union of love and wisdom takes place in every one of the most minute sections (if I may use the word) of the mind. Therefore, he was sure that a similar union of heart and lungs must take place in the body. In the absence of modern science, motion was the nearest he could get to actuality. Motion was, under the circumstances, a good word to choose, for it has suitable metaphorical meanings, e.g., "they were moved by the music"; "she put the motion before the meeting." So we are only supplying the necessary facts for the correspondence when we suggest that the motion is that of various components of the cells when, via the heart and blood, they receive oxygen supplied by the lungs. (The kind of motion we are thinking of here is not, of course, the Brownian motion by which diffusion takes place, but the many more special motions. An example is the movement of a phosphate group on to a glucose molecule, which occurs at the beginning of the cycle of events leading to oxidation of the glucose and a supply of energy to, say, a muscle.) 111. Can we imagine a more complete union between the lungs and the heart than this: that the heart pumps the blood through the lungs and then through the body, enabling the lungs to supply the essential oxygen (as well as to remove the carbon dioxide)? See Figure 2. And can we imagine a more complete dependence of every part of the body on the lungs as well as the heart beyond this: that without the oxygen from the lungs, brought by the blood, no part could move (in any sense) or exercise any orderly function or remain alive?(3) See Figure3. The collaboration of heart and lungs to bring refreshment to every smallest part of the body by means of the circulation is, I submit, a sufficient enough approximation to "influx" to be called "as it were an influx." Clearly also, the lungs rule, i.e., serve, all parts by means of the respiration, for even the extremities must receive their oxygen and be relieved of the carbon dioxide through the lungs. "According to the forms and according to the states" is simple enough from the physiological point of view. A muscle is a form different from bone. It requires more oxygen, and this requirement will depend on the state of the muscle, i.e., whether it is working or relaxed. These ideas can be pursued down to the molecular level, where a molecule will receive oxygen in one state, but not in another; but there is no need to go into detail. Thus, we find that the lungs ruling by the respiration agrees fully with modern thought, especially since, in a biochemical context, respiration refers to the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide at the cellular level.

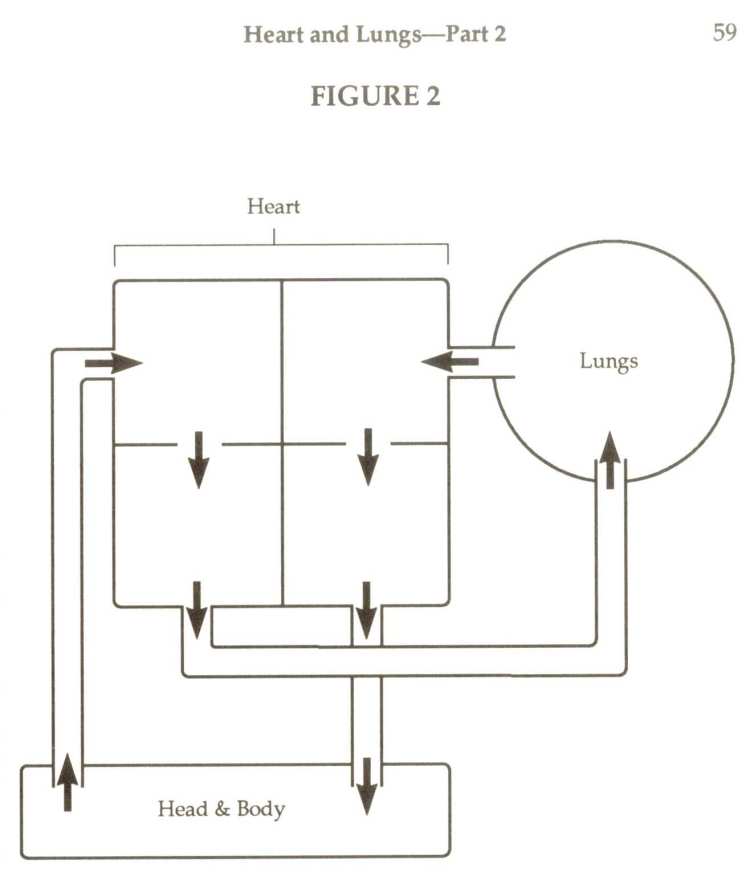

Circulation of the Blood Block diagram of circulation to show the separation of the two routes, lungs and body, and to illustrate that blood from the body cannot return to the body until it has passed through the lungs. See also Figure 3.

These examples show how natural knowledges

can lead to a more internal appreciation of truth

112.Although in the last section we have done no more than confirm what

certain passages from the Writings say about the heart and lungs of the

body, the exercise is more than mere confirmation. Confirmation is certainly

not to be despised, but having been given it, we are emboldened to step

out further. "The simplest statements [of the Writings] explored in depth,

yield arrangements of ideas which appear to stretch to infinity. Many of

these ideas may be understood only in terms of facts which Swedenborg the

man could not have known" (Newton, 1981). Hence, with the aid of doctrine,

and under Providence, we may use our natural knowledges to discover spiritual

truths reflected in natural facts (DLW 385)(4), and to

see truths which we might otherwise accept blindly. In such a way we may

gradually progress from external representatives towards more internal,

and therefore more excellent truths that we did not understand before.

Then we do not merely acquiesce in the truths of the Writings, but with

joy "draw water out of the wells of salvation" (Isaiah 12:3).

FOOTNATES 1 Rational is here used to mean a higher or spiritual level of the mind, not as used in the everyday sense--of a mind that thinks only from physical or sense experience and knowledge derived therefrom. 2 Clearly Swedenborg was obliged to write according to the knowledge his readers would have. Had he written according to the knowledges we now have, his works could not have been understood in his own time. In writing, the first necessity is to use a language the readers will understand. The second necessity is to use acceptable idioms; the third is a style of thinking not too foreign; the fourth is a background of beliefs and opinions that will not be offensive; the fifth--but how far can we go? It may even be necessary to include some erroneous beliefs to avoid becoming entirely incomprehensible to those who hold such beliefs. It has been said that a perfect revelation would be a miracle forcing belief and destroying freedom, but probably it would not do so. It merely would be incomprehensible, useless, a failure. The Word in Greek and in Hebrew contains many examples of Divine Truth accommodated in erroneous beliefs. 3 It is not surprising that, in an age when oxygen was not known and oxidation was not understood, the word "lungs" could be used to cover the whole phenomenon of respiration, and their movement could be regarded as of importance to the whole body. Even now, we find "lungs" being used in a vague way to mean apparatus for breathing, as in "iron lungs," for patients with paralysis of the muscles needed for breathing. |